Today, a military conflict can never be imagined to occur without electronic dimensions. Such dimensions are growing to be the core of any contemporary defense system in a possible present or future confrontation. It is expected to be similar to Russian-Georgian war in 2008, and Russian-Estonian war in 2007, which gave impetus to efforts undertaken by several countries, such as the United States, United Kingdom and China, as well as Israel, who tend to build their cyberwarfare forces and special electronic units, designated to defend and protect them against hundreds and thousands of professional hackers and cyber-attacks.

Cyber-attacks can be waged by a state, regular army, international organization, or military militia to attack cyber or information networks in a country, for example, to enforce a denial of basic services, such as disrupting electricity and lighting networks, or poisoning drinking water.

Moreover, Cyber warfare is not limited to jamming or infecting service facilities’ computers by malicious viruses, but cyber forces can also launch an operation to control the enemy’s defense systems or jam its satellites and paralyze advanced weapons system through, for example, a large-scaled or directed electromagnetic spectrum.

History of cyber warfare

The history of cyber warfare dates back to the cold war. In 1982 there was a rather interesting event called the Trans-Siberian Soviet Pipeline Sabotage. There was a massive KGB operation called Line X.

The Soviet empire was basically a couple of decades behind on technology and microelectronics design. KGB aimed to breach that gap by stealing all the IT for everything from the West. They trained basically an army of scientist moles to infiltrate companies, agencies, to steal blueprints. The CIA was tipped off, and instead of arresting all of them, CIA decided to launch counter-intelligence operation, based on the fact that they, having known who they are, CIA decided to let them keep operating, but feed them bad info. Feed them schematics for things that they can build. But a week, a month, maybe a couple of months after production line it would fall apart.

And this operation actually sabotaged Line-X on the inside, because they started doubting the veracity of the information given to them by their own moles. And, consequently, the whole thing just kind of fell apart. As for the Soviet Pipeline, the CIA was tipped off that the KGB mole was aiming to steal the SCADA system blueprint for pipelines, like big, natural gas, oil pipelines, and they were going to use them somewhere in Russia. CIA injected documents that had a little bug in the code, and it was basically a logic bomb that was set to fail. The Soviets took it, they built it, they implemented it in their backbone for natural gas and oil coming from Siberia. And what resulted is they caused the pipeline to explode in the critical fork. The resulting explosion was 1/3 of the size of Hiroshima.

US Cyber network

At present, the U.S. Army’s new “network” is already introducing new combat dynamics by virtue of bringing an ability to connect armoured vehicles, drones, helicopters, and dismounted soldiers on a single data-sharing system, a scenario which multiplies attack options, shortens sensor-to-shooter time, and integrates targeting sensors.

There are, however, substantial new risks attending these added advantages, given the growing extent to which weapons systems are interwoven by computer networks. Greater interoperability, range and intelligence-sharing capability also increasingly introduce a need to safeguard or “harden” these networks.

“We have to be able to defend our network and defend operations in cyber. Cyber is a critical part of every single program we bring together. This allows us to compete at a threshold below armed conflict,” Gen. Joseph Martin, Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, told an audience during a recent event at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies.

Increased networking can also mean a potential intruder can do more damage through a single point of entry, potentially making more combat-sensitive data vulnerable. This means the Army is taking new steps to prevent radio “jamming,” cyber network “hacking,” GPS-signal disruption, and other kinds of enemy interference from compromising integrated combat operations.

Cloud Connectivity

There are many elements to these kinds of hardening efforts. One of them starts with cloud migration. By enabling improved access to data in real time across otherwise segregated or dispersed “nodes,” cloud connectivity is already both enabling the Army network and changing combat tactics. As part of any cloud migration, developments are viewed through a two-fold lens; while the cloud brings unprecedented advantages, data pooling and sharing requires additional cyber protections. Should an intruder gain access to a portal of some kind, and have an ability to penetrate portions of a cloud-enabled network, greater volumes of data could be vulnerable from a single point of access.

Massive cyber breach

In December 2020, a U.S. cybersecurity company announced it had recently uncovered a massive cyber breach. The hack dates back to March 2020, and possibly even earlier, when an adversary hacked into the computer networks of U.S. government agencies and private companies via SolarWinds, a security software used by many thousands of organizations in the U.S. and around the world. New York Times cyber security reporter Nicole Perlroth calls the SolarWinds hack “one of the biggest intelligence failures of our time.” “We really don’t know the extent of it,” Perlroth says. “What we know is that this thing has hit the Department of Homeland Security — the very agency charged with keeping us safe — the Treasury, the State Department, the Justice Department, the Department of Energy, some of the nuclear labs, the Centers for Disease Control.” Perlroth says the fact that the breach went undetected for so long means that the hackers likely planted “back door” code, which would allow them to re-enter the systems at a later date.

Future planning

In a report by Mark Pomerleau, published in a special edition of the Cyber Defense Review, a journal produced by the Army Cyber Institute at West Point, Lt. Gen. Stephen Fogarty, commander of Army Cyber Command, provided a road map for where his organization is headed.

Fogarty sketched out three phases Army Cyber Command will undertake over the next 10 years, with the first reaching out to mid-2021.

By that time, the command hopes to realize the initial builds of new programs and formations, many of which have already been underway for some time.

Phase I: The main effort is the migration of ARCYBER’s headquarters from Fort Belvoir, Virginia, to Fort Gordon, Georgia.

“For the first time, the Army’s operational and institutional Cyber forces will enjoy unprecedented synergies by operating from a single, information power projection platform,” Fogarty wrote.

One relatively new entity is the 915th Cyber Warfare Support Battalion. Created in 2019, the battalion will consist of 12 teams that support brigade combat teams or other tactical formations. These “fly away” teams, as some officials call them, would help plan tactical cyber operations for commanders in theater, and unilaterally conduct missions in coordination with forces in the field. Officials previously noted that this formation will likely evolve over the years: As the force conducts operations and exercises, it may need to revisit its structure and capabilities.

The command will also undergo a reorganization to increase the number of available field information operations support teams, expanding reach-back and social media capabilities to both conventional and special operations forces, Fogarty wrote.

The last component of phase one, as described by Fogarty, is a new offensive cyber operations signal battalion. ARCYBER received approval to create the “long-needed” battalion, which will be at Fort Gordon in late 2021 and provide support to Army cyber forces.

Given this is a new entity, little information is available. However, Fogarty said it will reflect the mission previously performed by National Guard forces as Task Force Echo, for which details are also scare, except it’s known that the task force supports U.S. Cyber Command and the Cyber National Mission Force. The Cyber National Mission force conducts offensive cyber operations under the guise of defense to defend the nation from malicious cyber actors.

Phase II: Fogarty said phase two, which will take place between 2021 and 2027, is where the force will “experiment and innovate.” This phase will see the employment of the new capabilities and units created in phase one.

“As Army commanders gain increased ‘sets and reps’ integrating information capabilities into sustained operations, ARCYBER, in conjunction with [Training and Doctrine Command] and Army Futures Command (AFC), will serve as the Army’s key knowledge collector for emerging 21st century warfighting art in the [information environment],” Fogarty wrote.

During this phase, ARCYBER will create an information warfare operations center at Fort Gordon. The center will provide ARCYBER an “unprecedented,” real-time ability to sense and understand the global information environment with connectivity to all Army service component commands.

“This unique vantage point will allow ARCYBER to sense, understand, decide, and respond to emerging global IE conditions, providing options to Army senior leadership and regional Army and Joint Commanders with unmatched speed, enabling strategic decision advantage,” the authors wrote.

The creation of this new center is meant to directly benefit ARCYBER’s support to Cyber Command through Joint Force Headquarters-Cyber and the combatant commands for which it conducts cyber operations.

Critical to the success of the new operations center will be a specialized military intelligence brigade organic to ARCYBER, Fogarty stated. This brigade, which is not yet resourced, will focus on the information environment to include cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum. Fogarty also mentioned that as information warfare evolves, the missions of the offensive cyber teams that ARCYBER fulfills for Cyber Command through the 780th Military Intelligence Brigade could shift toward shaping the information environment.

The Army will also evolve its tactical forces by expanding the current cyber and electromagnetic activities, or CEMA, cells within the staff sections to include information operations, psychological operations and public affairs personnel. This cell works to inform and plan operations for the commander at echelon within the CEMA environment.

Along those same lines, the Army will work to optimize Reserve components. Fogarty noted that many of the information capabilities aligned to support conventional forces reside in the reserves. Fogarty also described a fair amount of experimentation that will occur in phase two. This will help inform the continued development of forces and capabilities to support multidomain operations. This experimentation will include:

The Multidomain Task Force, specifically ARCYBER, assisting in the training and readiness of the Intelligence, Information, Cyber, Electronic-Warfare, and Space Battalion.

A theater information command, which is an Army Futures Command concept for a two-star command, providing theater commanders with influence capabilities that will be tested during Joint Warfighting Assessments and Defender exercises.

The Information Warfare Task Force-Afghanistan, which was led by the Army Special Operations community, will conduct military information support operations, social media collection, data analytics and cutting-edge digital advertising technology for influence messaging.

Phase III: Phase three will take place from 2028 and beyond, and focus on multidomain capabilities. By this point, Fogarty writes that whatever Army Cyber Command becomes, it should be able to succeed in information and unconventional warfare, conduct intelligence and counter-adversary reconnaissance, and demonstrate a credible deterrent.

“As part of the Joint Force, the Army must master these essential Competition Actions through what [Multi-Domain Operations] MDO calls ‘active engagement’ to become MDO-capable,” they write. “In each critical task, ARCYBER will play an essential supporting role as the Army better develops its ability to conduct active engagement through the converged employment of maneuver and information capabilities focused on achieving desired cognitive effects and behaviors in our adversaries.”

Russia Cyber Force

Russia has deployed sophisticated cyber capabilities to conduct disinformation, propaganda, espionage, and destructive cyberattacks globally. To conduct these operations, Russia maintains numerous units overseen by its various security and intelligence agencies.

Early Russian Cyber Operations

According to media and government reports, Russia’s initial cyber operations primarily consisted of Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks and often relied on the co-optation or recruitment of criminal and civilian hackers. In 2007, Estonia was the target of a large-scale cyberattack, which most observers blamed on Russia. Estonian targets ranged from online banking and media outlets to government websites and email services.

Shortly thereafter, Russia again employed DDoS attacks during its August 2008 war with Georgia. Although Russia denied responsibility, Georgia was the victim of a large-scale cyberattack that corresponded with Russian military actions. Analysts identified 54 potential targets, (e.g., government, financial, and media outlets), including the National Bank of Georgia, which suspended all electronic operations for 12 days.

Russian Security and Intelligence Agencies

Over the past 20 years, Russia has increased its personnel, capabilities, and capacity to undertake a wide range of cyber operations. No single Russian security or intelligence agency has sole responsibility for cyber operations. Observers note that this framework contributes to competition among the agencies for resources, personnel, and influence, and some analysts cite it as a possible reason for Russian cyber units conducting similar operations, without any apparent awareness of each other. Additionally, some agencies appear to prioritize the development of in-house capabilities, whereas others look to contract outside actors for operations.

Chinese Views on Cybersecurity

China’s academic discussion of cyber warfare started in the 1990s when it was called “information warfare.” Impressed by how the US military benefited from the application of high technologies in the Gulf War—and subsequent operations in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq—China began to realize that there is no way to adequately defend itself without following the changes in the forms of war in which high technologies, mainly information technologies, play more critical roles.

In 1993, two years after the Gulf War, the Chinese military adjusted its military strategic guideline which set “winning local wars in conditions of modern technology, particularly high technology” as the basic aim of preparations for military struggle (PMS). In 2004, one year after the Iraq War, the military’s PMS was changed to “winning local wars under conditions of informationization.” The basic understanding, as elaborated in China’s National Defense in 2004, is that “informationization has become the key factor in enhancing the warfighting capability of the armed forces.”

The first time that the Chinese military publicly addressed cyber warfare from a holistic point of view was in the 2013 version of “The Science of Military Strategy”—a study by the Academy of Military Science. It emphasized that cyberspace has become a new and essential domain of military struggle in today’s world. A similar tone appeared in the 2015 Ministry of National Defense paper entitled “China’s Military Strategy.”

While the latter document modified the basic point for PMS to “winning informationized local wars,” it also addressed cybersecurity for the first time in an official military document. It defined cyberspace as a “new pillar of economic and social development, and a new domain of national security,” and declared clearly that “China is confronted with grave security threats to its cyber infrastructure” as “international strategic competition in cyberspace has been turning increasingly fiercer, quite a few countries are developing their cyber military forces.”

Based on the above approach that China is taking to cyberspace and its own national security, a few conclusions can be drawn. The first is that China has not developed its cyber capabilities in a vacuum. Rather, they have developed them as a response to the changing cyber warfare approaches and practices of other countries, especially those of the US and Russia. The second is that the Chinese government’s views on cyber warfare are consistent with its military strategy, which is modified according to the national security environment, domestic situation, and activities of foreign militaries.

Basic Aims of China’s Cyberwarfare

Though there is no commonly accepted conception of cyber warfare, one made by a RAND Corporation study is frequently quoted by Chinese military analysts: cyber warfare is strategic warfare in the information age, just as it was nuclear warfare in the 20th century. This definition serves as the foundation to argue that cyber warfare has much broader significance to national security and involves competition in areas beyond the military, such as the economy, diplomacy, and social development.

Again, China’s Military Strategy describes the primary objectives of cyber capabilities to include: “cyberspace situation awareness, cyber defense, support for the country’s endeavors in cyberspace, and participation in international cyber cooperation.” The strategy frames these objectives within the aims of “stemming major cyber crises, ensuring national network and information security, and maintaining national security and social stability.”

Of these objectives, an essential one is national security and social stability. The Chinese government’s monitoring of the internet and social media is based on its potential use as a platform to disseminate information that could cause similar social unrest to spread, which could lead to large-scale social and political instability.

Another essential objective, in common with all states, is defending critical information infrastructure. China is more and more dependent on information networks in all aspects, including in defense. Although it has a large-scale technology industry and possesses the potential to compete with the US in some, most of its core network technologies and key software and hardware are provided by US companies.

China uses the term “eight King Kongs” to describe the top internet companies in its domestic supply chain: Apple, Cisco, Google, IBM, Intel, Microsoft, Oracle, and Qualcomm. Heavy dependence on these companies’ products makes it necessary to work towards developing the domestic technology industry and its capabilities, and to thereby make the country’s internal internet infrastructure more secure. It also makes China believe that its primary mission in cyberspace is to ensure information security of critical areas, which is inherently defensive and non-destructive.

The overall defensive perspective of the government is ultimately in line with China’s strategic guidelines and its understanding of the general characteristics of cyber warfare. China has consistently said that it adheres to the strategic guideline of Active Defense, as elaborated in the 2015 defense paper. Guided by these principles, the primary stated goal in cyber warfare is to enhance defense capabilities in order to survive and counter after suffering an offensive cyber strike.

Buildup of Cyber Capabilities

Cyber warfare encompasses far more areas than the military and intelligence gathering. It is therefore logical to measure one country’s cyber capability by a more comprehensive evaluation, which at least includes: technological research and development (R&D) and innovation capabilities; information technology industry companies; internet infrastructure scale; influences of internet websites; internet diplomacy and foreign policy capabilities; cyber military strength; and comprehensiveness of cyberspace strategy. If evaluated along all these criteria, China’s cyber power largely lags behind that of the US.

Aside from China’s disadvantages in critical technological self-sufficiency as mentioned above, it is not as advanced in other aspects as well. According to the ICT Development Index (IDI), which is based on 11 indicators to monitor and compare developments in information and communication technology across countries, China respectively ranked 80th, 81st, and 82nd among 176 states in 2017, 2016, and 2015.

Part of China’s low influence on the global internet is due to the fact that its primary languages are not widely used on the internet outside the country. Though there are a massive number of Chinese speakers throughout the world, Chinese languages are only used by 1.7 percent of all websites, while 53.9 percent use English.

According to an article published by International Peace Institute’s Global Observatory, China’s internet is also one of the most regularly attacked. According to a report published in February 2019 by Beijing Knownsec Information Technology, China suffered the highest rate of distributed denial of service attacks (DDOS) in the world in 2018—an average of over 800 million a day. Scanning and backdoor intrusions made up the majority of the attacks and about 97 percent were conducted by domestic hackers. However, a growing percentage came from overseas, mostly from the US, South Korea, and Japan. Among all the attacks originating overseas, those that targeted government and financial websites largely outnumbered those on other targets.

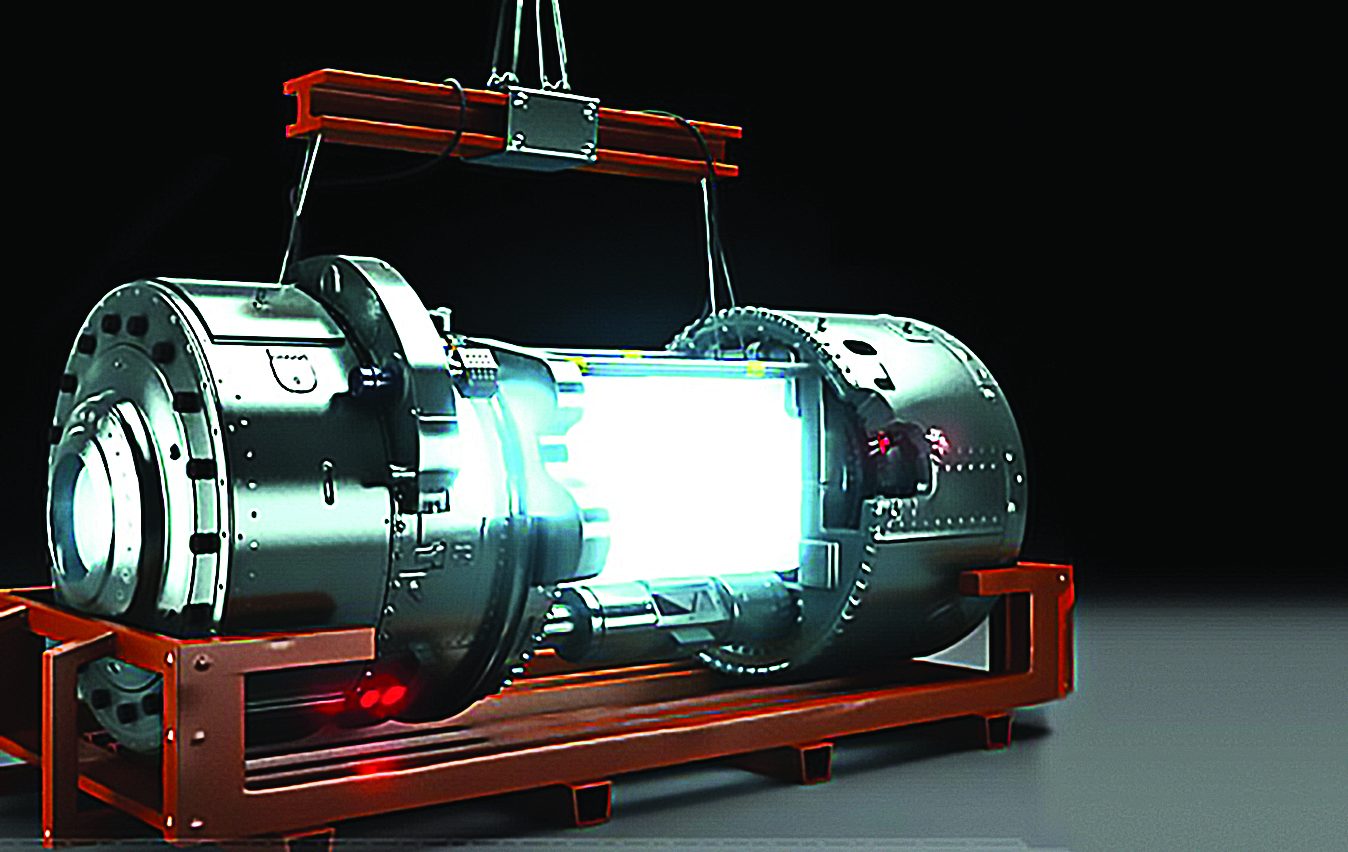

Electromagnetic Armament Race

The U.S. Army is developing a new tool to gain an advantage in the cat and mouse game that is the electromagnetic spectrum mission.

Currently in the early concepts stage, the Army detailed its idea for the Modular Electromagnetic Spectrum Deception Suite, or MEDS, that will seek to confound the enemy within the invisible yet highly dynamic maneuver space of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Despite the fact forces cannot see it, the spectrum is an extremely important space they must cautiously move through just as a unit would in formation through a valley. U.S. adversaries have proven their ability to locate units based solely on their signature in the electromagnetic spectrum, leading to entire concept and material changes for the Army to smaller units and command posts.

Deception within the spectrum has become a high priority for the U.S. military.

MEDS is expected to both see the enemy and slow its decision cycle by overwhelming its forces within the spectrum, said Steven Rehn, director of the Army’s cyber capability development and integration directorate.

According to Rehn, one purpose of MEDS is to replicate friendly emissions within the spectrum from the small unit level all the way up to a full corps command post, which could cause the enemy to waste time and resources figuring out if it is a real entity.

In addition to replicating friendly signals, MEDS could also create more “noise” within the spectrum to potentially slow down the enemy.

Russia’s Super Weapon

The latest intelligence indicates that Russia has specialized a “super-electromagnetic pulse” weapon and warhead capable of traveling at Mach 20.

Peter Vincent Pry, executive director of the EMP Task Force on National and Homeland Security, also said China has leapfrogged U.S. developments in electromagnetic pulse warfare.

EMP weapons are exploded high enough up in the atmosphere to wipe out the electric grids and computers in huge sections of the country. The outages could last over a year, he said. In his report, Pry also said China had surpassed the U.S. in EMP warfare development.

Parity with the US

The fight for electromagnetic spectrum superiority has been ongoing for over a century, said Marcus Clay, an analyst with the U.S. Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute.

The U.S. military’s domination of the spectrum has steadily declined over the past two decades. This is mainly because American defense planners and warfighters have been preoccupied with non-peer adversaries operating in a highly permissive spectrum environment. In the same timeframe, China has been making moves to strengthen its electromagnetic spectrum-enabled capabilities, and has brought itself to near parity with the United States.

Mechanism of EMS

From radio waves to gamma rays, the electromagnetic spectrum covers the entire range of light that exists. Modern militaries use radars and other sensors to locate each other and the enemy, wireless computer networks to order supplies and coordinate operations, and jammers to degrade enemy radars or disrupt communications that are critical for effective command and control. The spectrum is what ties everything together.

In the Department of Defense’s Electromagnetic Spectrum Superiority Strategy, released last year, the spectrum is identified as an enabler of military operations in other domains, not as an independent warfighting domain in its own right. China follows this development closely and likely shares this assessment at present. Circumstantial evidence suggests that the People’s Liberation Army is also likely crafting its own high-level spectrum strategy. Chinese military strategists increasingly prioritize the exploitation and domination of the electromagnetic spectrum in their evolving military doctrines. To deter China’s adversaries both militarily and psychologically, they advocate the deeper integration of computer networks into electronic warfare, with such capabilities to be used alongside precision kinetic strikes. Anticipating a fast-paced future battlefield, China also appears poised to apply advanced technology such as AI and machine learning to the task of strengthening its electronic warfare capabilities.

AI & Machine Learning

The advancement of AI and machine learning can significantly accelerate the processing of thousands of unknown, new, and unusual emitters that exist in a complex and constantly changing electromagnetic spectrum battlefield.

Although electromagnetic energy is invisible and intangible, it is also prevalent and measurable, while also sensible and controllable. This creates a broad space for the employment of stratagems. Chai Kunqi, likely affiliated with China’s hypersonic weapons program, describes electronic warfare as a “cat and mouse” game and “an exciting landscape of modern warfare that showcases the strategic wisdom of the opposing forces.”.

Unpredictable Age

The age of bipolar cold-war is over. We now live in an unpredictable age where “speed” is the most important element of power. Expert in cyber security and author Dr Armistead E. Leigh, in his book “Information Operation: Warfare and the Hard Reality of Soft Power”, said: `What the future holds for military forces, and the national security establishment is unclear”. The age we live in is unpredictable.