Climate change has made access to the Arctic and utilisation of its resources viable, thus this region has attained great geostrategic importance in recent years. What is the geostrategic significance of the Arctic region? Are there updates in the military strategies of states towards the region given climate developments? How do these powers interact in the region, amid current geopolitical developments? How will global competition in the region affect the change in the international strategic and military map?

This study aims to provide initial answers to these questions and to achieve this, it is divided into two parts: The first clarifies the geostrategic importance of the Arctic while. the second analyses aspects of the growing militarisation of the Arctic and the geopolitical developments that led to this. Finally, we explore its implications.

First: The Arctic’s Geostrategic Importance

In 2008, a study by the United States Geological Survey indicated that the Arctic polar region may contain around 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil resources and 30% of undiscovered global gas resources. Furthermore, global warming is melting Arctic ice every year, allowing for the gradual opening of new shipping routes. This could shorten the distance between Rotterdam and Yokohama by 40% compared to passing through the Suez Canal.

On the other hand, the Northwest Passage, off the coast of Canada, could also significantly reduce the distance between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

To enable cooperation between regional states, the Arctic Council was established by the Ottawa Declaration signed in 1996 by Canada, Denmark, the United States, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia and Sweden.

The Council is the leading intergovernmental forum for regional cooperation on Arctic issues. However, it is not a governing body but rather a forum for cooperation between Arctic states.

Moreover, it does not address military and sovereign issues outside its mandate, focusing instead on topics likely to achieve consensus easily, such as scientific cooperation, environmental protection, indigenous welfare and economic development, maritime safety, etc. In addition to the eight Arctic states, six Indigenous Peoples Organizations representing Arctic indigenous peoples have permanent participant status.

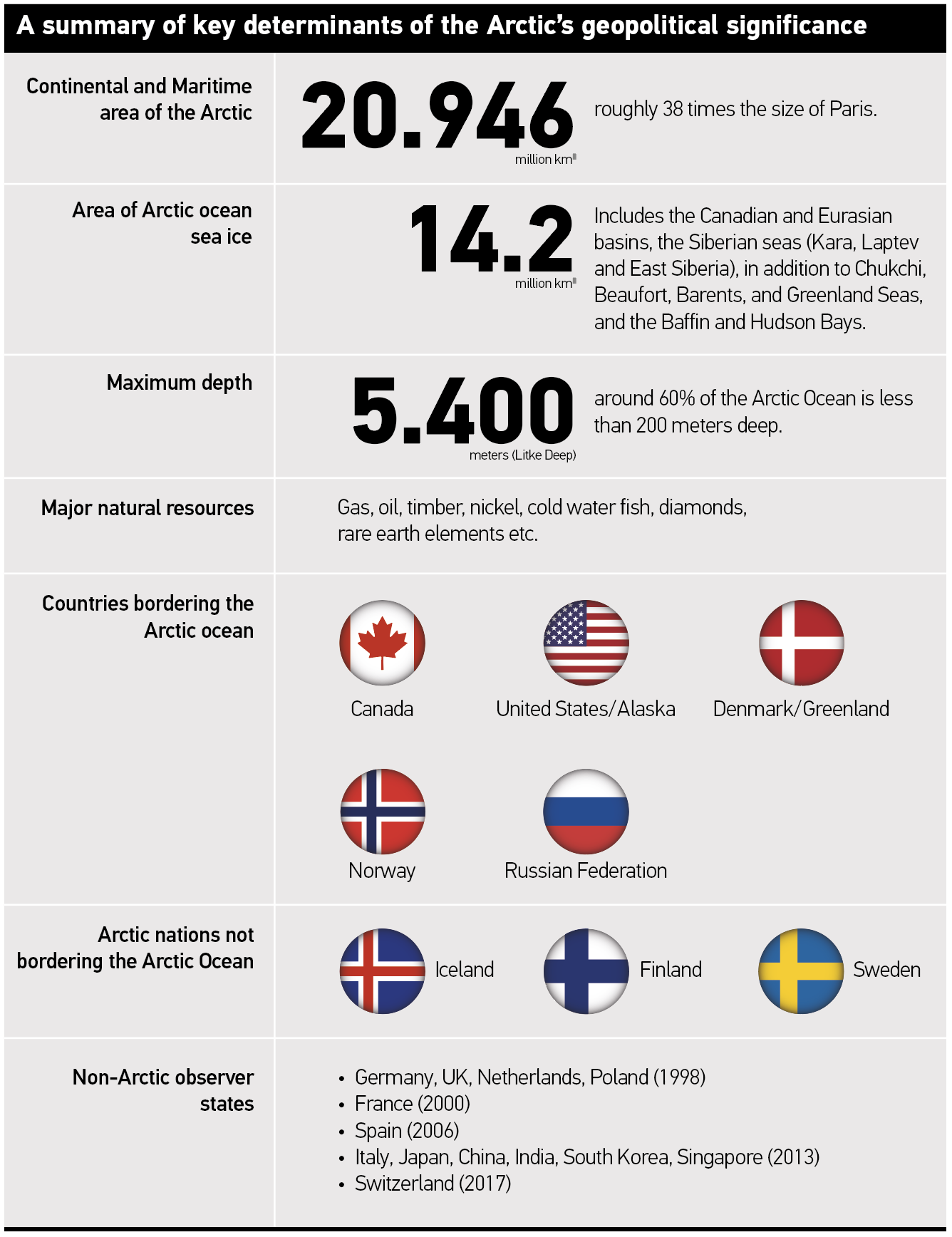

There are also non-Arctic observer states like Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Poland, France, Spain, Italy, Japan, China, India, South Korea, Singapore, and Switzerland, as well as numerous other international organizations such as the United Nations through some of its environmental and development programs.

Moreover, a recent study projected that the Arctic could become nearly sea ice-free by the early 2030s, even under a low emissions scenario, which is roughly a decade sooner than previously expected. According to the latest projections, Russia will possess around 41% of undiscovered oil and gas reserves, while the United States (via Alaska) will possess 28%.

Second: the increase in the pace of militarization of the Arctic in light of the current geopolitical development

In 2022, during a press conference in Canada, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg emphasized the importance of the Arctic region for NATO’s security.

He stated that Russia is using the region to test its hypersonic missiles and military capabilities, as well as systematically flying its aircraft over the area.

Stoltenberg noted that melting ice makes the region more important than ever, stressing the need to harness it militarily and economically.

He also affirmed the importance of enhancing Canada’s military presence in the region and its positive impact on the security of Europe and its allies.

Regarding the impact of the Russia-Ukraine war on military balances in the Arctic, Dr. Lawson Brigham, a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, stated that the Arctic, which has seen countries join NATO following the war, has become a stage for militarization more than ever, for the following reasons:

1- Finland and Sweden joining NATO means 7 of the 8 Arctic nations are now part of NATO. This will make military and security cooperation between Moscow and other Arctic states difficult, if not impossible.

On the other hand, Finland and Sweden joining NATO will certainly change the alliance’s plans and push for more deterrence capabilities and military development in the region.

2- The future of the Arctic Council, established in 1996, is more uncertain than ever. With the exception of Russia, the Council’s members decided to suspend its work following the Russian war on Ukraine. The other seven states affirmed their support for the Council but stated their intention to resume work within its framework, excluding the projects that involve Russia’s participation.

3- One Arctic state, the United States, remains outside the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, and the implementation of many articles relevant to the Arctic Ocean remains contentious among member states, raising concerns about regional stability.

4- Some border disputes between Arctic nations remain unresolved, most importantly between the United States and Russia, the United States and Canada, and Norway and Russia.

The above has led to increased focus on the accelerated pace of militarization and the demand for security, as well as strengthening states’ military capabilities in the region.

On the Russian side, Russian forces in the Arctic are centred around the 200th Motor Rifle Brigade, the 80th Brigade, and the 61st Naval Infantry Brigade.

The 200th and 80th Brigades will likely be consolidated into one division, with the creation of separate powerful formations such as a Missile Brigade, an Air Defence Brigade, and others.

Moreover, Russia’s Ministry of Defence has decided to form a new army comprised of all military divisions that will be part of the Northern Fleet covering Russia’s northern borders, including Finland and Norway.

This army’s objectives include protecting the strategically critical Kola Peninsula, where Russia’s nuclear ballistic missile submarines are based.

The Russian Armed Forces also regularly conduct drills in the polar latitudes, especially the annual Umka manoeuvres involving individual training and polar research.

For example, in 2021 a detachment of ships from the Northern Fleet trained in amphibious landings in various parts of the Arctic, with marine infantry units storming polar coasts.

Furthermore, Russia continues to reinforce its Northern Fleet, equipping it in recent years with its newest vessels. It now includes the newest Project Borei strategic missile submarine and the multi-purpose Project 885 (Yasen-M) nuclear submarine armed with Kalibr cruise missiles. The latter will soon be equipped with the hyper-sonic Tsirkon missile.

More coastal defence systems like the Bal and Bastion are now deployed on Arctic islands, more polar airfields have been rebuilt, and more Russian forces are expected to be steadily transferred to the Arctic from other land and naval areas.

The Arctic region also hosts more than a third of Russia’s nuclear warheads.

Moreover, Finland and Sweden’s move to join NATO is expected to compel Russia to establish a new army to address the new situation and increase the pace of combat training in Arctic conditions.

On the American side, the Biden administration last year presented an updated version of the national strategy for the Arctic until 2032, to first, enhance the U.S. military presence in the Arctic; second, intensify training with partner countries; and third update air defence to deter aggression in the Arctic, mainly from Russia.

The United States also concluded a new bilateral defence agreement with Norway and is negotiating similar agreements with Finland, Denmark and Sweden.

Additionally, the American military presence in Iceland is evolving. Joint military exercises between American forces and those of Norway, Finland and Sweden are also increasing.

In early 2024, the U.S. Defense Department will announce a new Arctic strategy that appears to be a tougher response to growing Russian and Chinese military activity in the region and indications of an intensifying alliance between them, especially off Alaska’s coast.

On the other hand, recent years have seen increasing interest from NATO in the Arctic region. NATO Military Committee Chairman Admiral Rob Bauer has stated that NATO must prepare for emerging military conflicts in the Arctic.

He expressed his concern about the increasing competition and militarization in the Arctic region, especially by Russia and China.

(NATO and Russia’s lack of an effective high-level military hotline to de-escalate any sudden, unforeseen rise in tensions, exacerbates matters), he added.

In 2022, there were three major NATO exercises in the Arctic:

(Operation Nanook) naval exercises in northern Canada in August-September, led by Canada with participation from the U.S., France and Denmark.

The (Adamant Serpent) Special Forces exercises in September, led by U.S. Special Forces in Europe, with participation from Canada, Finland, Norway, Sweden and the UK. As part of the exercises, Norwegian and American special forces trained together in the inland areas of Tromsø, northern Norway.

The (Joint Viking) land exercise in March led by Norway, and its maritime extension (Joint Warrior) led by the UK, in northern Norway, which saw the participation of 11 allied nations.

Norway holds wide-ranging exercises every two years involving over 30,000 military personnel and more than 200 aircraft and 50 ships.

In 2009, Norway moved its military joint operational headquarters from the south of the country to Bodo in the north and invested in new frigates and joint strike fighters.

Denmark established an Arctic joint northern command centre in Nuuk, Greenland, at the heart of the Arctic.

Sweden recently hosted (Arctic Challenge 21), one of Europe’s largest air force exercises, with participation from the U.S., Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK.

These exercises aimed to conduct a full range of air defence, close air support, air defence penetration and air-to-ground bombing exercises in the Arctic sky.

In March 2015, Norway and Sweden signed an agreement to increase their defence cooperation in the Arctic.

For its part, Canada announced in 2022 through Defence Minister Anita Anand that it will be upgrading its air and missile defence systems in the Arctic in cooperation with the United States.

A budget of 4.9 billion Canadian dollars (3.6 billion euros) has been allocated over 6 years for this purpose.

The minister attributed these new measures to the (growing military threats) from Russia and the emergence of new enemy technologies like hypersonic missiles.

She noted that this new budget represents the most significant upgrade in almost 4 decades. The money will be spent on building ground radars and satellites capable of detecting bombers or missiles, plus sensor networks with (classified capabilities) to monitor approaching air and sea objects from the Arctic to shore.

The new systems will replace the old North Warning System dating back to the Cold War era, whose 50 stations can no longer detect modern missiles.

In March of the same year, the Canadian government announced its intention to purchase 88 F-35 fighter jets from the U.S. to replace its ageing fleet and conduct patrols in the Arctic.

The Arctic represents not only an area for cooperation or conflict amongst its coastal states but has also become a region targeted by distant nations like France and China, which consider themselves (near-Arctic states).

In recent decades, China has established itself as a major power in the Arctic and strengthened its ability to change geopolitical and geoeconomic balances in the region.

China defines itself as a (near-Arctic state) suffering from the melting of the frozen ocean. In January 2018, Beijing published its White Paper on the Arctic Polar Silk Road and China’s Arctic Policy, defending its right to navigate in the region.

However, China also clarified that it has no territorial claims in the Arctic and does not intend to impose its power over it. After five years of negotiations and two failed attempts, Beijing managed to obtain permanent observer status on the Arctic Council in 2013.

Despite this, former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo did not hide his concern about the Chinese presence in the Arctic at a 2019 meeting with Arctic Council members.

He emphatically stated, (There is no such thing as a near-Arctic state. You are either an Arctic state or you are not), in reference to American discomfort with China’s presence on the Council as an observer member.

Notably, China has invested around $12 billion in Russia’s Yamal Arctic gas field located in the Kara Sea, one of the world’s largest liquefied natural gas projects.

When fully operational, it is expected to double Russia’s output. China thus owns 30% of the Yamal field, divided as follows: 20% by the China National Petroleum Corporation and 10% by the Silk Road Fund.

China is also investing in various other places in the Arctic, which usually precedes a direct or indirect military presence to protect such interests, especially in a region like the Arctic.

France’s main defence and security interests in the Arctic appear to be fundamentally economic, security and environmental.

Thus, any attack on the stability and security of the Arctic area, which represents a pioneering frontier for mineral resource exploitation, energy and a future transit area between Asia and Europe, could affect France’s current and future interests.

This involves ensuring the security of its energy supplies and more specifically strategic metals essential to the high-tech defence industry (niobium, tantalum, etc.)

France is aligned with Arctic region nations due to its membership in the European Union (Denmark, Finland and Sweden) and NATO (Canada, the United States, Denmark, Iceland, Norway), and is therefore concerned about stability and security in this region located 2,500 to 5,000 kilometres from the French coast.

France sees the gradual opening of sea routes in the Arctic, and the increase in commercial traffic in which vessels flying the French flag will participate, as posing new challenges that will require: protecting and rescuing ships, combatting pollution, fundamental legal issues relating to freedom of navigation, etc.

Finally, the Arctic area provides manoeuvring space for the French navy. At an operational level, the French armed forces believe they must remain able to use the Arctic region for their air and naval forces.

Finally, a French nuclear submarine and support vessels, which were recently docked in Tromsø, northern Norway, are carrying out long-term missions in the Arctic.

Moreover, France has participated in numerous naval exercises in the Arctic region, most importantly Formidable Shield, Dynamic Mongoose and Joint Warrior.

In conclusion, observing the following map showing military bases in the Arctic region demonstrates the extent of militarization this part of the world has undergone.

Conclusion

The pace of Arctic militarization appears set to accelerate in the coming days, as evidenced by recent events:

In August 2023, Russia and China conducted a joint naval patrol near Alaska but did not specify the number or location of ships. In response, American newspapers cited a Defence Department official saying 4 U.S. destroyers – USS John McCain, USS Benfold, USS John Finn and USS Chung-Hoon – and a P-8 Poseidon aircraft tracked the movements of these ships.

On September 17, 2023, Russian Foreign Ministry Special Envoy Nikolai Korchunov stated that Russia will respond to NATO bolstering its military presence in the Arctic with a set of measures.

The next day, the Russian Defence Ministry published footage of drills conducted by the Russian army north-east of the Bering and Chukchi Seas in the Arctic, around 50 km from Alaska.

The ministry said around ten thousand troops and over 50 military units participated in the drills, which included nuclear-powered submarines launching cruise missiles.

Moscow said the objective of these drills was to test its readiness for a potential conflict in its northern icy waters and protect the Northern Sea Route.

NATO Military Committee Chairman Rob Bauer announced what he called the (Arctic threat) from China and Russia during the Arctic Circle Forum, considering that (Russia and China have caused accelerated military competition in the Arctic).

Factors further accelerating Arctic militarization also include the growing conviction among international players in the region that:

(Whoever controls the Arctic controls the world), as stated by Admiral Valery Aleksin in 1995.

The coming years will determine the shape the Arctic will take for a long time to come.

The rapid melting of the Arctic ice not only makes access to the Arctic’s natural resources easier, but also brings Europe, Russia, and North America face to face in a new space for confrontation after the ice separating them melts.

» By: Professor Wael Saleh (Expert at Trends Research & Advisory Center)