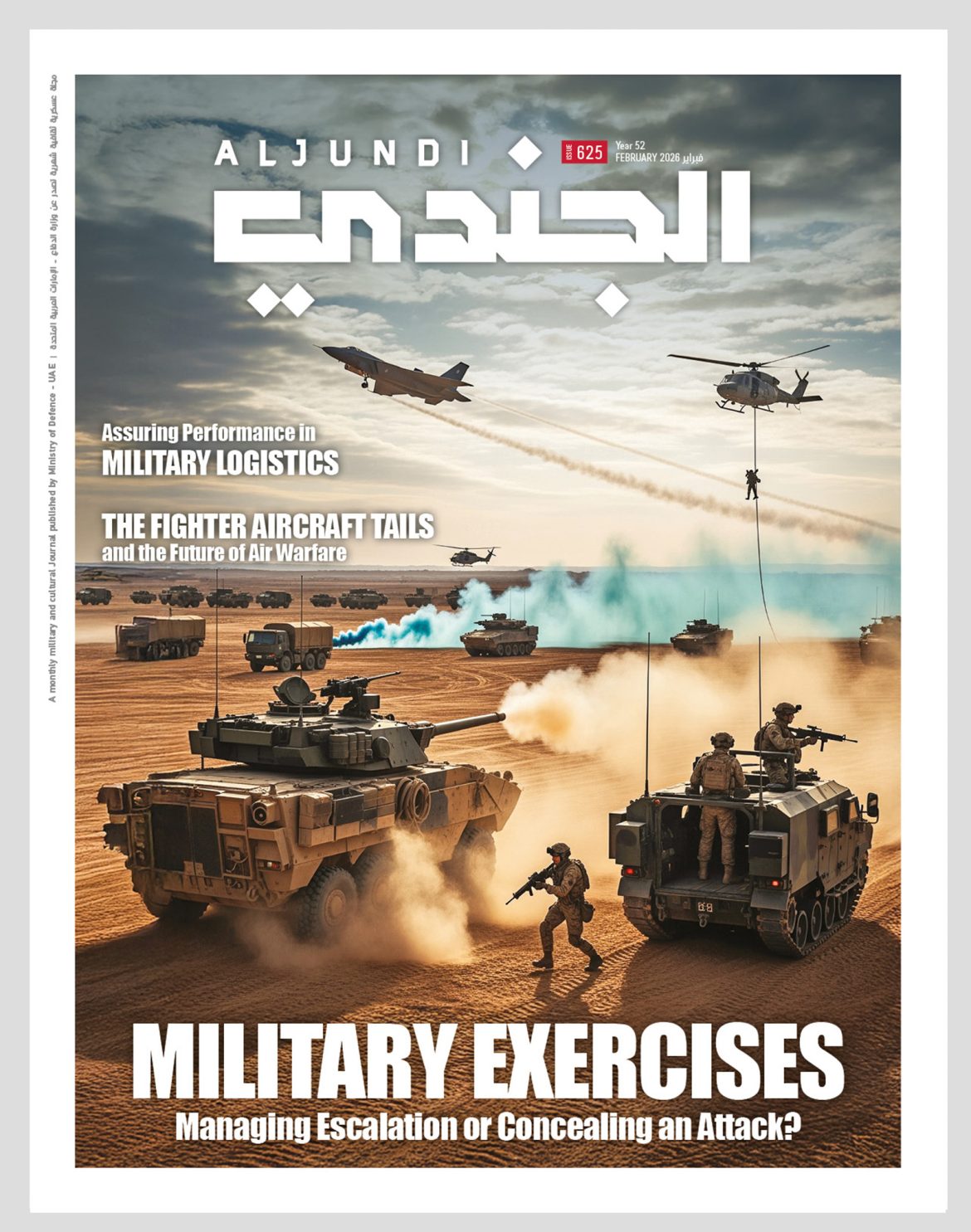

Joint military exercises have emerged as one of the most prominent forms of military cooperation in the contemporary security landscape. Over the past decade, the frequency and scale of these exercises have increased markedly, with an average of one major drill conducted approximately every nine days. This dramatic rise has sparked debate about their implications for the international system. While some argue these exercises provoke adversaries and heighten the risk of military conflict, others contend that they serve as a deterrent, reducing the likelihood of escalation and conflict.

Today’s global security architecture is characterised by complex, interdependent networks in which nations exchange economic goods and defence-related services. Within these networks, defence institutions interact through two main channels: conflict and cooperation. The cooperative dimension—often described as “defence diplomacy”—encompasses a wide spectrum of peaceful engagements, including ministerial visits, multilateral collaboration, arms sales, industrial partnerships, and joint military exercises.

Joint military exercises involve the participation of two or more countries, with objectives ranging from sharing tactical knowledge and improving weapons proficiency to preparing forces for various operational scenarios, such as adverse terrain or extreme weather. These drills typically focus on a specific mission—whether countering armed groups, enhancing marksmanship, or responding to weapons of mass destruction—while fostering interoperability and coordination among diverse units.

There are two primary categories of joint exercises:

• Command Post Exercises (CPX): Conducted at headquarters, these simulations employ advanced computer systems and do not involve actual deployment of large-scale equipment such as tanks or fighter aircraft.

• Field Training Exercises (FTX): These involve real-time, on-ground training using operational units and equipment to simulate live mission scenarios. Participants may range from small detachments to full-scale military formations.

Training scenarios can be either combat-related, such as NATO’s Cold War-era “Autumn Forge” and “Reforger” exercises, or non-combat in nature, addressing humanitarian crises, natural disasters, peacekeeping, or law enforcement.

While joint exercises initially served to enhance traditional combat readiness—particularly during the Cold War—the evolution of warfare has expanded their scope. Modern drills now often incorporate non-traditional missions such as counter-terrorism, peacekeeping, and humanitarian assistance, falling under the umbrella of “Military Operations Other Than War” (MOOTW).

The past three decades have witnessed a significant increase in both the number and diversity of joint exercises. Since 1990, all global regions except South America have recorded a steady rise in these drills. In 2016, the number of joint exercises reached approximately 300—six times the total recorded in 1990. The trend accelerated further following the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, culminating in a record number of joint drills in 2022. Among the most prominent was “Vostok 2022”, a large-scale exercise led by Russia and China with participation from India, Belarus, and Tajikistan, noted for its geographic scope and extensive troop involvement.

Four Key Metrics for Assessing Joint Military Exercises

Joint military exercises can be evaluated and categorised using four principal criteria:

1. Complexity: Exercises involving multiple countries are inherently more complex than bilateral drills. Complexity also rises when exercises focus on high-intensity warfare, such as anti-submarine operations. Moreover, complexity levels vary depending on the operational readiness of participating countries. For instance, submarine warfare training is less complex for nations like the U.S., Australia, or Japan, compared to Indonesia, where military readiness is primarily focused on internal security.

2. Sustainability: Sustainable exercises are those institutionalised over time and conducted at regular intervals. They tend to have greater strategic value and reflect deeper levels of commitment and operational integration.

3. Utility: This refers to the extent to which exercises address the actual security needs of participating nations. Given varying operational capacities and strategic priorities, each state derives different benefits, balancing collective objectives with individual strategic goals.

4. Diversity: The range of partners a nation trains with influences its strategic flexibility. Smaller or medium-sized states often diversify their partners to avoid over-reliance on a limited set and to access a broader spectrum of training expertise.

Strategic Drivers Behind Joint Exercises

The proliferation of joint military exercises is not merely a response to rising global conflict. Nor does it align with an increase in formal military alliances. Instead, nations are engaging in these drills for their multifaceted benefits, ranging from tactical improvements to strategic signalling.

At the tactical level, joint exercises enhance operational compatibility between armed forces, ensuring smooth coordination in communications, logistics, and battlefield manoeuvres. These engagements facilitate the adoption of new tactics and technologies, aligning different military doctrines for collective action.

At the strategic level, exercises serve as tools of defence diplomacy. They can reassure allies, deter adversaries, and signal commitment or defiance. For example, the joint U.S.-South Korea drills following North Korea’s intercontinental ballistic missile launch in February 2023 were a clear signal of solidarity and readiness. Similarly, “Vostok 2022” sent a strong signal of alignment between Russia and China amidst international isolation following the Ukraine conflict.

Joint exercises can also be used to:

• Enhance military capacity, as seen in the EU-Indonesia drills in the Arabian Sea, to bolster anti-piracy operations.

• Develop operational experience in unique environments, as demonstrated by Finland’s “Freezing Winds 2022” exercise, conducted under harsh weather conditions.

• Promote trust and repair diplomatic ties, exemplified by the “Falcon Strike” exercises between China and Thailand, resumed in 2022 after a pandemic-induced pause.

Additionally, major powers often use joint drills to showcase and market their military hardware, leveraging these platforms to expand arms sales and establish strategic partnerships.

Beyond Training: A Foundation of Military Diplomacy

Joint exercises reflect a significant level of defence relationship maturity between participating states. Such exercises require not only technical compatibility but also strategic alignment and mutual trust, as nations expose sensitive military doctrines, capabilities, and tactical approaches during training. Hence, they are rarely the first step in a defence partnership. Instead, they typically follow defence cooperation agreements and a series of high-level visits and strategic consultations.

U.S.–China Rivalry and the Expanding Landscape of Joint Exercises

The United States remains the dominant global partner in joint military exercises, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. Between 2003 and 2022, Washington participated in approximately 1,113 joint exercises with 14 regional states, highlighting its entrenched role as a security provider. However, China has been steadily asserting itself as a credible alternative. During the same period, Beijing conducted around 130 joint exercises in the region, signalling its intent to rival U.S. influence despite having fewer formalised defence partnerships.

There are notable distinctions in approach. U.S.-led exercises tend to be more complex and focused on integrated warfare, especially maritime and air operations. Conversely, China’s joint drills often prioritise land-based operations, counter-terrorism, humanitarian assistance, and disaster relief. These differences reflect divergent strategic priorities: while the U.S. uses joint training to reinforce leadership credibility and deter adversaries, China aims to build trust with regional partners and expand its institutional military networks.

Both powers now serve as central nodes in the Asia-Pacific’s military exercise network, leveraging their logistical capabilities to project influence. The military adage “train where you may fight” encapsulates the strategic intent behind these exercises, especially amid rising concerns over potential conflict scenarios involving China and the U.S. in the region. Western reports suggest that China’s growing operational tempo, alongside accelerated military modernisation, could erode America’s long-held superiority in the Asia-Pacific. Despite current gaps in combat experience, China’s emphasis on field exercises is intended to close that gap. As Washington doubles down on its own training commitments, Beijing is moving swiftly to consolidate regional military ties.

Joint Exercises as Instruments of Structural Change

Analysts have increasingly scrutinised the role of joint military exercises in influencing the international system’s architecture. Some Western assessments warn that the surge in training activities could increase the risk of miscalculation and conflict—particularly in the absence of established alliances. The 2008 war in South Ossetia serves as a case in point. Just one month after Georgia’s participation in the multinational “Sea Breeze” exercise, which involved five NATO member states, Georgian forces launched an operation in South Ossetia. Perceived Western backing may have emboldened this decision, contributing to the conflict with Russia.

On the other hand, NATO’s Cold War-era REFORGER exercises, conducted annually throughout the 1970s and 1980s, did not result in escalation with the Warsaw Pact. This contrast underscores a key point: the escalatory potential of joint exercises is often tied to whether the participating states are part of an established military alliance.

Although joint exercises are inherently less explicit than formal defence treaties, they serve as powerful signals of strategic alignment—particularly when major powers participate alongside smaller or mid-tier states. These exercises are now a key dimension of what might be termed “military diplomacy,” used to project commitment and shape the security environment without necessarily invoking treaty obligations.

The Sino-Russian Convergence and Its Strategic Implications

China and Russia, united in their opposition to a U.S.-dominated global order, have significantly deepened their defence cooperation through joint exercises. While such collaboration began under the auspices of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in 2003, it gained notable momentum after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. Although the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily slowed this trend, joint exercises have surged again since the onset of the Russia–Ukraine war.

Recent drills have grown in complexity and operational depth, featuring joint command centres, airborne deployments, and the use of each other’s advanced military hardware. These exercises now simulate regional conflict scenarios and reflect a high level of strategic trust and coordination, potentially laying the groundwork for future joint operations aligned with shared geopolitical goals.

There is also a visible shift in the geographic focus of Sino-Russian exercises. While earlier drills were more evenly distributed, recent activities have increasingly taken place in East Asia—particularly in the East China Sea—while diminishing in European waters. This change reflects the constraints on such exercises in Europe and a strategic pivot to areas of higher geopolitical tension.

The scope and location of these drills have expanded dramatically. Exercises have been conducted near geopolitical flashpoints such as the South China Sea, the Mediterranean, and even the coasts of Alaska and Japan. Notably, in 2023, Chinese and Russian naval vessels manoeuvred near Okinawa and Miyako at the very time a trilateral summit brought together leaders from the U.S., Japan, and South Korea—an unmistakable signal of defiance.

September 2024 saw the launch of “Ocean 2024,” a major Russian-Chinese joint exercise that deepened Western anxiety. This followed a series of similar exercises earlier that year, including near Japan and off the Alaskan coast. Analysts argue that these activities reflect a growing pattern of enhanced military coordination amid regional instability and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. As Russia’s influence wanes in certain regions, China appears poised to fill the vacuum—expanding its military footprint and strengthening partnerships through joint training.

A New Global Military Architecture

Traditional military alliances were once the primary vehicle for reordering the global balance of power—especially during the Cold War. However, joint military exercises now appear to be emerging as a more flexible and less costly alternative. Their adaptability aligns well with today’s rapidly evolving international system.

The surge in joint exercises coincides with increasing discourse about the need to restructure the global order. These drills are not merely tools for preparedness—they are instruments for shaping the future. By sending calibrated signals and building operational interoperability, joint exercises are helping to recalibrate the balance of power.

In conclusion, joint military exercises have become a core component of today’s international order. They influence how states prepare for threats, form partnerships, and pursue strategic interests. As military diplomacy continues to evolve, joint exercises are likely to play an even more prominent role in the emerging global security framework—serving as a preferred mechanism of deterrence over traditional alliances or overt conflict. Their accelerating pace suggests that their significance will only grow in the years ahead.

By: Adnan Moussa

(Assistant Lecturer, Faculty of Economics and Political Science – Cairo University)