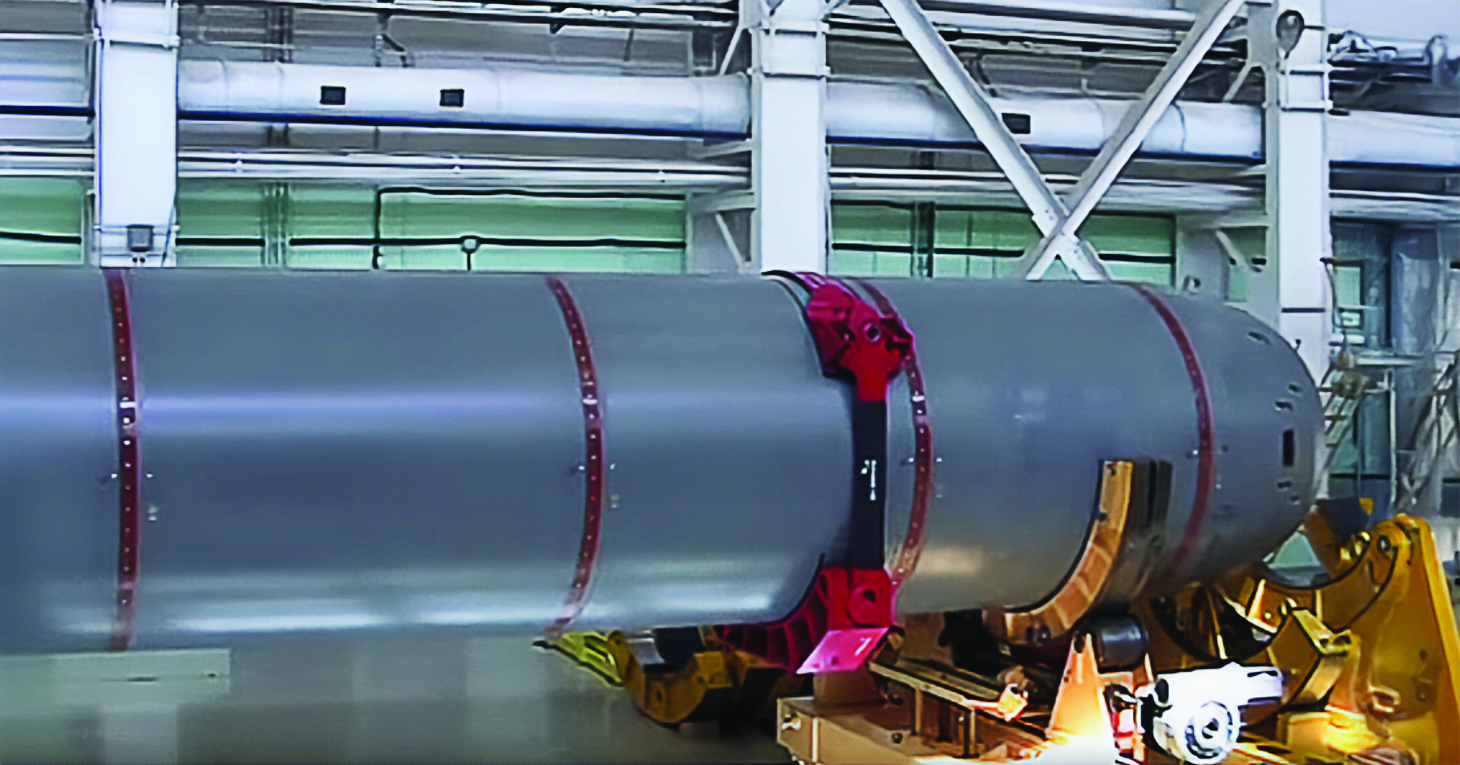

In March 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin unveiled six advanced strategic weapons during his annual State of the Nation address. The announcement came as a direct response to Washington’s expanding missile-defence systems, which Moscow views as undermining strategic parity. Among the weapons showcased were two systems that would later become central to global strategic debates: the 9M730 Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile-described at the time as having “unlimited range”-and the 2M39 Poseidon, an unmanned, nuclear-powered torpedo capable of travelling up to 10,000 kilometres. Both systems rely on nuclear propulsion and can be fitted with nuclear warheads, representing a profound shift in the character and risks of strategic deterrence.

Putin presented an animated video showing the Burevestnik flying low over oceans, evading air-defence systems, and striking a target near Hawaii. True to its name—“storm petrel,” a seabird known for its long, low-altitude flights—the missile is designed to travel close to the surface to avoid detection. By late October, Chief of the Russian General Staff Valery Gerasimov announced that the Burevestnik had completed a 14,000-kilometre test flight, signalling significant progress in a programme that many analysts had long viewed with scepticism.

In the same month, Putin revealed that Russia had also successfully tested the Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo, calling the results “remarkable.” He emphasised that the torpedo’s destructive potential exceeded even that of the Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile and that “no countermeasure” currently exists to intercept it. Together, these developments suggest that Russia has taken a decisive step toward fielding a new generation of nuclear-powered strategic weapons—systems that could shift the global nuclear balance and have far-reaching implications for international stability.

Early Attempts and Technical Barriers to Nuclear Propulsion

The concept of nuclear-powered engines for long-range missiles dates back to the Cold War. Between 1957 and 1964, the United States pursued nuclear ramjet technology through Project Pluto, aimed at developing a supersonic, low-altitude nuclear-powered cruise missile capable of penetrating deep into Soviet territory. The programme was eventually cancelled due to the extreme risks posed by its unshielded reactor, which leaked radiation during testing.

A 1959 report by Project Director Theodore Merkel, “Nuclear Ramjet Propulsion,” outlined the most critical challenges. Chief among them was the need for a reactor that was both compact and robust—light enough to fly, yet strong enough to withstand severe thermal and pressure changes, as well as the forces generated during manoeuvring and acceleration. Similar concerns were raised two years earlier by Soviet defence scientists, who also warned of the limitations imposed by materials capable of resisting the extreme temperatures expected within the reactor.

Both Soviet and U.S. studies noted that a nuclear-powered cruise missile would likely require an auxiliary propulsion system for takeoff, adding further complexity. Nuclear reactors are inherently heavy and operate at high temperatures—conditions that run counter to aerodynamic efficiency. Moreover, a nuclear engine is mechanically complex and highly vulnerable to failure. Cooling such a reactor in flight would require additional design compromises, including a larger air-intake system, which would in turn release hazardous radioactive particles into the atmosphere.

Despite these formidable engineering obstacles—and decades of U.S. retreat from the concept—Russia has persisted, ultimately achieving breakthroughs that Western analysts once deemed nearly impossible.

From Concept to Capability: Russia’s Development Journey

The formal unveiling of the 9M730 Burevestnik in October 2025 was unsurprising to U.S. intelligence agencies, which had been tracking the programme for years. Putin first announced the missile in 2018, claiming it would fly at very low altitudes, possess near-unlimited range, and follow unpredictable trajectories, rendering it “invincible” against both current and future missile-defence systems.

In January 2021, the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) referenced the missile for the first time—under NATO’s reporting name “Skyfall”—in its ballistic and cruise missile assessment. Washington identified three test sites associated with the programme: Kapustin Yar, Nyonoksa, and Pankovo. The earliest signs of the programme emerged at Kapustin Yar in 2016, where U.S. intelligence designated it under the provisional code KY-30. Analysts now believe that development has been ongoing since at least 2010.

Progress was far from smooth. In August 2019, an explosion at a Russian military facility in Arkhangelsk—linked by Rosatom to the testing of a “liquid-propulsion system containing radioactive isotopes”—killed five engineers. The accident underscored the inherent risks of experimenting with compact nuclear reactors. Yet despite setbacks, Russia pressed ahead. By October 2025, Putin declared the Burevestnik’s latest test a success, calling it a “unique system unmatched by any other country.”

U.S. intelligence assessments suggest that the road to success was long and difficult. By early 2019, the United States had documented thirteen Russian attempts to test Burevestnik prototypes—eleven of which failed shortly after launch. The primary technical obstacle was the transition from the initial booster engine to the nuclear reactor, a delicate mode-switching phase that caused most failures. Even the two relatively successful flights lasted only minutes and covered limited distances.

Moreover, U.S. analysts initially concluded that many tests were undertaken at Putin’s insistence, contrary to the advice of engineers from Novator—the firm responsible for missile development—and the research centre overseeing nuclear propulsion. These assessments suggested internal doubt among Russian specialists regarding the feasibility of the programme.

Nonetheless, NASIC’s 2020 report concluded that, if Russia succeeded in fielding a functional nuclear-powered cruise missile, it would gain a “unique, intercontinental-range nuclear capability.” This aligns with the assertive rhetoric of Russian officials, even as some Western experts continue to question the operational value of such systems.

Implications for Global Strategic Stability

Russia’s progress in developing nuclear-powered strategic weapons marks a potential turning point in the evolution of global deterrence strategies. The combination of unlimited range, unpredictable flight paths, and nuclear endurance challenges the traditional missile-defence architecture upon which the United States and its allies rely.

Unlike ballistic missiles, which follow predictable trajectories, a nuclear-powered cruise missile could approach U.S. territory from virtually any direction, including over the South Pole—an approach largely uncovered by existing radar networks. Meanwhile, the Poseidon’s deep-sea mode of operation allows it to bypass traditional anti-submarine and missile-defence systems entirely.

Such capabilities could upset strategic stability by introducing weapons that blur the lines between deterrence, escalation, and ambiguity. They also raise significant safety concerns, including environmental contamination risks during testing or operational deployment.

In this context, Russia’s achievements may prompt the United States and other nuclear powers to reconsider dormant nuclear-propulsion technologies, potentially reigniting an arms race in systems once considered too hazardous to pursue.

The Nuclear-Powered Autonomous Torpedo

In November 2025, Russia’s Ministry of Defence announced the launch of its new nuclear submarine Khabarovsk, described as a platform “designed to conduct missions for the Navy using various types of unmanned underwater systems.” According to the announcement, one of those systems is expected to be the experimental nuclear-powered Poseidon torpedo, unveiled by President Vladimir Putin just days earlier, on 29 October.

Admiral Vyacheslav Popov, former commander of Russia’s Northern Fleet (1997–2001), stated that commissioning Khabarovsk effectively marks the operational debut of the new Poseidon system—named after the ancient Greek god of the sea, storms, and earthquakes.

Western assessments note that—if Russia’s claimed capabilities prove accurate and the system enters serial production—Poseidon could fundamentally reshape nuclear deterrence. It is widely regarded as one of Russia’s most dangerous new strategic weapons: a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed, autonomous torpedo capable of striking coastal cities with catastrophic effect.

Russia, however, emphasises that Poseidon could also serve as a tactical nuclear weapon against high-value naval assets such as aircraft carriers, describing it as a “multi-purpose system.” Nevertheless, its strategic significance lies in its role as a survivable second-strike weapon, designed to ensure Russia’s ability to respond to a nuclear attack.

Poseidon’s reported performance underscores these concerns. Western intelligence estimates its maximum speed at roughly 70 knots, far faster than current torpedoes, making interception highly improbable. Its operational depth is believed to reach 1,000 metres, a range that further complicates any attempt to track or destroy it. This would require NATO to develop entirely new categories of anti-subsurface weaponry—an undertaking that demands substantial time and investment.

Another key advantage is its nuclear propulsion system, which gives Poseidon virtually unlimited range. This allows unpredictable launch positions and diverse attack trajectories, although its mission profile is likely limited to destroying naval formations or coastal population centres—targets such as New York or Los Angeles are frequently cited in Western analyses.

Moscow’s Strategic Objectives

Russia’s unveiling of Burevestnik and Poseidon serves multiple strategic and political purposes vis-à-vis the United States and its allies. Several key objectives can be identified:

1. Defeating U.S. Missile Defences (“Trump’s Golden Dome”): General Valery Gerasimov emphasised that during Burevestnik’s test flight, all planned vertical and horizontal manoeuvres were executed successfully, demonstrating its ability to evade missile-defence and air-defence systems.

The overarching goal is to deliver a nuclear cruise missile with intercontinental range—theoretically between 10,000 and 20,000 km—capable of reaching U.S. territory from virtually any launch point in Russia. Unlike conventionally powered cruise missiles, which must fly at medium altitude to conserve fuel, the nuclear-powered Burevestnik can fly at extremely low altitudes (50–100 metres) without risking fuel exhaustion.

Flying “under the radar,” literally and figuratively, allows it to exploit terrain masking and avoid known Western air-defence sites through highly circuitous routes.

U.S. strategic missile defence systems—primarily based in Alaska and California—are designed to intercept ballistic missiles in the stratosphere. Their effectiveness against low-flying, nuclear-powered cruise missiles is, by design, extremely limited.

According to Gerasimov, Burevestnik’s initial test covered 8,700 miles over more than 15 hours, at altitudes of just 100 metres—a flight profile that allows it to infiltrate Western airspace undetected.

2. Reinforcing Russia’s Claim to “Nuclear Superiority”: The U.S. plans to deploy its first Dark Eagle hypersonic missile batteries by December 2025—approximately eight years after Russia first introduced its own hypersonic systems, and just as Moscow works on a second generation, including the Oreshnik system.

Yet almost immediately after Washington announced progress on hypersonics, Moscow revealed its new nuclear-powered systems—Burevestnik and Poseidon—both of which President Putin insists are effectively impossible to intercept. He has repeatedly stated that: “There is nothing like it in the world. Competitors are unlikely to appear anytime soon, and no interception methods currently exist.”

From Russia’s perspective, the United States does not possess—and has no active programme to develop—nuclear-powered missiles. This places Washington in a reactive position: forced either to pursue similar technologies or to invest heavily in new defensive systems capable of countering these weapons.

The cost implications of either path are enormous.

Deputy Chairman of Russia’s Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev, captured this sentiment bluntly: “Unlike Burevestnik, Poseidon can be considered a full doomsday weapon.”

President Putin has likewise asserted that Poseidon’s destructive capacity is “far greater” than even the Sarmat hypersonic ICBM. Unlike intercontinental ballistic missiles, Poseidon remains immune to any existing missile-defence architecture and can deliver a nuclear warhead to virtually any coastal city on Earth.

3. Containing Military Escalation in Ukraine: Russia has leveraged its advantage in next-generation missile production—particularly hypersonic systems—to deter the West from escalating the conflict through the Ukrainian front. This dynamic was evident during the administration of former U.S. President Joe Biden, who, in the final phase of his term, signalled his intention to supply Ukraine with Tomahawk cruise missiles. Moscow’s response came swiftly in November 2024, when it launched its newest medium-range ballistic missile, the Oreshnik, armed with a non-nuclear hypersonic warhead, against a military-industrial installation inside the Ukrainian city of Dnipro.

President Vladimir Putin justified the strike, framing it as retaliation for Ukrainian attacks—executed with long-range American and British weapons such as ATACMS and Storm Shadow—on military sites in Russia’s Bryansk and Kursk regions. The Kremlin also threatened an “appropriate response” should Tomahawks be transferred to Ukraine. This pressure ultimately pushed the Biden administration to back away from the idea.

A similar pattern unfolded when the Kremlin publicised Burevestnik and Poseidon, both nuclear-powered strategic systems, at the same time the current U.S. administration under President Donald Trump was considering supplying Ukraine with Tomahawks. The messaging was clear: these advanced weapons were unveiled to warn the West of the escalatory risks associated with providing such missiles to Kyiv. The strategy appears to have worked. On 3 November, President Trump stated explicitly that he was not considering any deal that would give Ukraine long-range Tomahawks for use against Russia. Should the U.S. position remain unchanged, Moscow would have succeeded in persuading Washington to avoid a move that could have ignited not only heightened confrontation between Moscow and Kyiv but also between Moscow and Washington.

Russia further reinforced its deterrence posture by revising its nuclear doctrine during the Russia–Ukraine war. In November 2024, Moscow lowered its declared threshold for nuclear use, maintaining the right to launch nuclear retaliation in response to any conventional attack that poses a “serious threat” to the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Russia or Belarus. It also warned that an attack carried out by a non-nuclear state with support from a nuclear-armed state would be treated as a joint attack, while any strike by a member of a military alliance would be considered aggression by the entire bloc.

This means that any U.S. support enabling Ukraine to strike strategic targets inside Russia with Tomahawks would give Moscow grounds—under its revised doctrine—to employ nuclear weapons against both Ukraine and the United States. Given Russia’s lead in hypersonic systems and nuclear-powered delivery vehicles, such threats carry significant weight in Western, and especially American, calculations.

4. The Beginning of a New Arms-Race Era: In early November 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump issued directives to conduct nuclear weapons tests “to ensure nuclear parity with Russia and China,” claiming that other states were carrying out secret nuclear tests—an implicit reference to Russia and China. Trump’s statement was misleading, as neither country has conducted nuclear tests. His remarks drew a sharp response from Moscow. President Putin reiterated Russia’s continued commitment to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) but warned that Moscow would take “symmetrical measures” if the United States proceeded with nuclear testing.

The U.S. position created confusion, as neither Russia nor China conducts nuclear tests. What both countries engage in is the testing and development of nuclear delivery systems, such as missiles. This suggests Trump may have been referring to missile tests involving nuclear-capable platforms rather than actual nuclear detonations. Supporting this interpretation, the U.S. Army announced shortly after Trump’s remarks that it had conducted a test of a Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile capable of carrying a nuclear warhead—a system that has been in service since 1970.

Despite these statements and steps, Washington does not appear prepared to enter a new arms race and, if anything, seems intent on avoiding that path. This became evident when President Trump subsequently floated the idea of U.S.–Russia–China cooperation on a nuclear disarmament framework. Implicitly, his message was an invitation to de-escalate and open the door to possible dialogue.

Conclusion

Through the development of the Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile and the Poseidon nuclear-powered unmanned torpedo, Russia has demonstrated its ability to overcome major technical barriers and produce entirely new generations of strategic weapons based on technologies no other state has yet attained. These advances reinforce a military lead that began in 2017, when Moscow outpaced Washington and the West by fielding the world’s first operational hypersonic missile.

It is no exaggeration to say that Burevestnik and Poseidon have disrupted the strategic balance with the United States by introducing unprecedented nuclear delivery systems. Washington will now be compelled to respond, either by developing comparable capabilities or creating defensive systems designed to counter these new threats.

At the same time, the Kremlin has used these two systems to underscore its strategic superiority over Washington and to set limits on the extent of U.S. military support to Ukraine. This enhances Moscow’s ability to ensure that its objectives in Ukraine are achieved—whether by force or through negotiation. And although the deployment of these advanced Russian weapons could signal the emergence of a new global arms race, the risk remains constrained for now by President Trump’s inclination to avoid entering a nuclear arms build-up.

By: Dr Shadi Abdelwahab – (Associate Professor, National Defence College)